Winnaretta

The American-born Winnaretta Singer [1865-1943] was a millionaire at the age of eighteen, due to her inheriting a substantial part of the Singer Sewing Machine fortune. Her 1893 marriage to Prince Edmond de Polignac, an amateur composer, brought her into contact with the most elite strata of French society. After Edmond's death in 1901, she used her fortune to benefit the arts, science, and letters. Her most significant contribution was in the musical domain: in addition to subsidizing individual artists [Boulanger, Haskil, Rubinstein, Horowitz] and organizations [the Ballets Russes, l'Opéra de Paris, l'Orchestre Symphonique de Paris], she made a lifelong project of commissioning new musical works from composers, many of them unknown and struggling, to be performed in her Paris salon. The list of works created as a result is long and extraordinary: Stravinsky's Renard, Satie's Socrate, Falla's El Retablo de Maese Pedro, and Poulenc's Two-Piano and Organ Concertos are among the best-known titles. In addition, her salon was a gathering place for luminaries of French culture such as Proust, Cocteau, Monet, Diaghilev, and Colette.Many of Proust's memorable evocations of salon culture were born during his attendance at concerts in the Polignac music room. Sylvia Kahan brings to life this eccentic and extravagant lover of the arts, whose influence on the 20th Century world of music and literature remains incalculable.

Childhood

Winnaretta Eugenie Singer was born in Yonkers (New York State) on 8 January 1865. Her father was Isaac Merritt Singer, the American industrialist who perfected the sewing machine. He married a very young French woman, Isabelle Eugenie Boyer.

Isabelle Singer

Winnaretta spent her first two years of life in a mansion called "The Castle," but, in 1867, Isaac Singer, moved to Isabelle's home town of Paris. In 1870, with the Franco-Prussian War approaching, the Singers moved again, to southern England. Singer bought an enormous property in Paignton, South Devon, which he named "The Wigwam." This sumptuous residence of over 100 rooms included every modern convenience and also contained a large theater and a circular space that was used for circus performances.

After Isaac Singer's death in 1875, Isabelle Singer returned with his family to Paris. A family legend says that the beautiful Isabelle was the model of the sculptor Frédéric Bartholdi for the Statue of Liberty.

Winnaretta dressed for the presentation at the British court, 1905

Statue of Liberty- New York

He claimed that there was a ducal title in his family history and, soon after the marriage, the Singer fortune enabled Reubsaet to "rediscover" (that is, buy) the title of Duc of Camposelice. The Camposelices purchased a large mansion on Avenue Kléber. Victor used part of his wife's fortune to amass an extraordinary collection of rare stringed instruments, including the Stradivarius and Guarnarius violins owned by Vieuxtemps. The "grand salon" of the mansion became the center of musical and artistic meetings where the most famous performers were regularly to play string quartets of Beethoven, Mozart and Schubert. Winnaretta shared her mother's passion for music.

According to her memoirs, she received no special training outside her piano lessons, but she attended the many concerts in the family living room. On the occasion of one birthday, she asked for, as a gift, a performance of her favorite piece of Beethoven, the String Quartet in C-sharp minor, op. 131. The late Beethoven quartets were regarded as incomprehensible by most listeners, but already Winnaretta was showing evidence of taste, originality and a deep love for music.

Winnaretta studied painting in the studio of Prix-de-Rome winner Félix Barrias, and was fortunate to spend some time in the studio of Manet. Winnaretta became an accomplished painter, and, later in life, her paintings were often mistaken for those of Manet.

Winnaretta and her painting, Santa Maria dela Salute (Venice,1902)

She spoke French and English, and in 1882, at age 17, she was invited by the Department of the Louvre to participate in the preparation of the catalog in English.

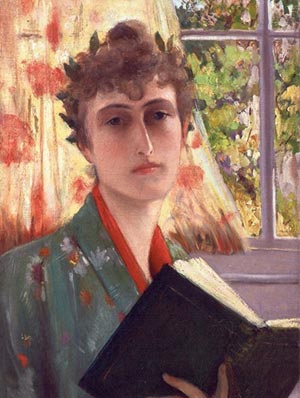

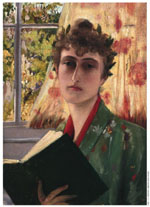

Winnaretta self portrait

At age 15 she developed a deep friendship with Gabriel Fauré, who was then 35. He was the first musician friend; she became his confidante and later his benefactor. In 1882, she accompanied her mother and stepfather to Bayreuth to attend a performance of Parsifal; from that moment on she was a passionate admirer of Wagner's music. For many years thereafter, she returned to Bayreuth, staying at "Schloss-Fantasie".

Venice

Early in their marriage, Winnaretta introduced her husband to Venice. Soon Edmond too was bewitched by the seductive calm of the lagoons; he would claim, “Venice is the only city where you can have conver¬sations in front of the open windows without having to raise your voice.” During a visit to Venice in 1900, they were invited to lunch by a wealthy American couple, Mr. and Mrs. Daniel Curtis. Cousins of John Singer Sargent, the Curtises lived in the Palazzo Barbaro on the Grand Canal, near the Accademia Bridge. Relaxing on the Curtis’s balcony after the meal, Edmond realized that he was sitting directly across from his favorite among all the palaces that lined the Grand Canal, a fine Lombard edifice known as the Palazzo Contarini dal Zaffo. When he saw it from the Curtis’s balcony, Edmond spontaneously exclaimed, “Ah! that is the place to live in, and we must manage to get it in one way or another!” Winnaretta was amazed: her husband so infrequently asked for anything at all. It was the week of his birthday, and she decided to buy him the present of a lifetime. The next day she went to see a real estate agent.

After a few months of wrangling, Winnaretta was able to secure the pur¬chase of the palace, which would henceforth be known as the Palazzo Contarini-Polignac.

Palazzo Contarini Polignac on the Grand Canal in Venice

The couple took possession in January 1901. Winnaretta’s first purchase for the palazzo was a pair of Giandomenico Tiepolo frescoes, Un sacrificio pagano and Un trionfo romano, dating from around 1760 and transferred to canvas. Unfortunately, Prince Edmond, always in frail health, died only eight months after the Polignac took possession of the Palazzo, shortly after his 67th birthday. The princess found herself deeply saddened by the loss of the man who had been her best friend and had played an important role in the world of art and beauty she had created around them.

Winnaretta returned to Venice in February 1902. She spent the afternoon hours sitting on her balcony, painting the Church of the Santa Maria della Salute, whose dome took on the colors of the twilight. She sought a musical venue through which to honor Edmond; eventually, she asked the Duca della Grazia, the owner of the Palazzo Vendramin, Richard Wagner’s former residence, if she could use his palace for a memorial concert.

The Duke consented, and Winnaretta arranged to have the Venetian Municipal Band play Siegfried’s Funeral March from Wagner’s Götter¬dämmerung, in the courtyard underneath the windows of the room where the composer had died. Winnaretta recalled the day in her memoirs:

It was a bright sunny day . . . and the Grand Canal looked its best; all the neighbouring houses had decked their balconies and windows with the brilliant hangings which were usually brought out on great occasions, and many of the best-turned-out gondolas in Venice (belonging to the great patrician families of Venice)—at least a hundred—guided beauti¬ful ladies to the steps of the Vendramin Palace. The Banda Municipale played the Funeral March very creditably, the guests crowding round the windows that looked on to the Cortile, and after the concert there was a buffet in the big central room or sala. I thanked the Duke profusely for all the trouble he had taken to have my wish carried out, and asked him how many years Liszt and Wagner had been his tenants.

He replied: “Oh, quite a long time—for seven years, at least, off and on; they spent many months here.” “And did you often see them?” I asked. “Oh, yes, they frequently came up to have coffee with us after dinner.” I was much impressed, and added: “And what did they do, and what did they say?” “They sometimes talked about music, or played the piano.” “Oh, how marvellous to have known these great men. What a wonderful experience!” The Duke replied, ca¬sually, “Oh yes, they were two characters.”

Marriage and Music

After the settlement of Isaac Singer's will, Winnaretta's inheritance made her a fabulously wealthy young heiress. However, life in her parents' home had become untenable, as her stepfather, the so-called Duc, was prone to violence. The day she turned 21, Winnaretta established her financial independence. She bought a large hôtel at the corner of Avenue Henri-Martin and Rue Cortambert. Realizing that she could not circulate in polite society as a single woman, she married the first man who proposed to her, Prince Louis of Scey Montbéliard. Winnaretta, who had always possessed an independent spirit, was delighted to escape from the guardianship of a domineering mother, but she was not happy in her married life. It was during this period that she probably affirmed to herself her lesbianism. However, it was as the Princesse de Scey-Montbéliard that she established her first musical salon. A large salon was used for orchestral concerts; a smaller atelier was used for painting and for chamber music concerts.

In Winnaretta's music rooms,

The Music Room at the Hôtel Singer-Polignac, Paris ca. 1912

On 1 February 1892, the Vatican officially annulled the Scey Montbéliard marriage. At the end of that year, Count Robert de Montesquiou and his beautiful and influential cousin Countess Elisabeth Greffuhle encouraged Winnaretta to remarry and find a respectable position in aristocratic society. The man they chose for her was their friend, Prince Edmond de Polignac, twenty years Winnaretta's senior, a talented but impoverished composer from one of the oldest families in France.

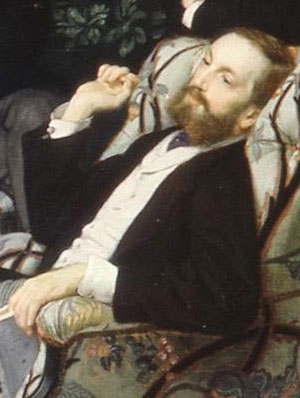

Prince Edmond

Prince Edmond de Polignac

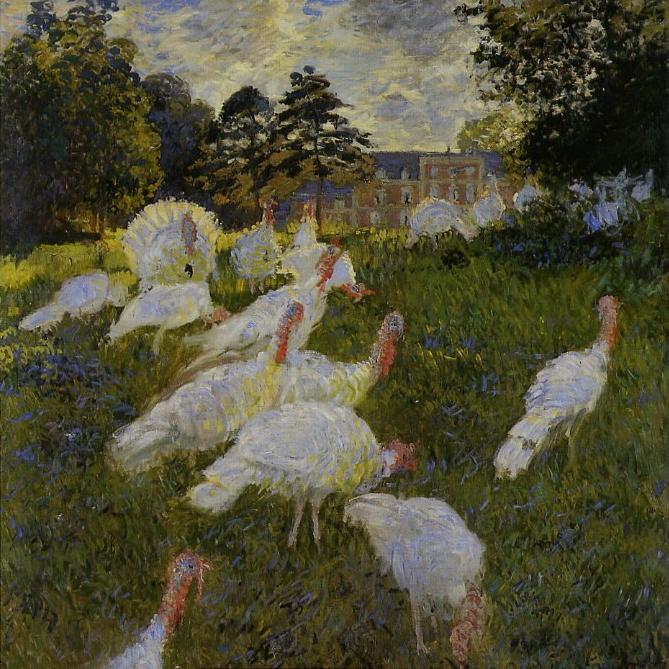

According to Marcel Proust, who had met the Prince through Montesquiou, both Winnaretta and Edmond had attended the same auction, bidding against each other for a Monet canvas, Champs de tulipes en Hollande. Winnaretta won the painting. Although Prince Edmond was enraged at the time to have been outbid by an American women, he joked later on that "I married the American and could look at the painting as often as I liked."

Claude Monet, Champs de Tulipes en Hollande

Life in Music

Winnaretta Singer-Polignac spent the rest of her life living for music and, thus, honoring the memory of her beloved husband. In 1904, she renovated her Paris mansion, creating a music room large enough to comfortably accommodate a chamber orchestra and 200 guests. The large living room of 43 Avenue Henri Martin was reserved for major orchestras and renowned artists, while the workshop Cortambert proposed street concerts with organ accompaniment and more intimate musical evenings. Meanwhile, the salon of the Princess de Polignac reflected the thriving artistic activity of his time. A dozen times a year, artists and aristocrats would gather for a sumptuous dinner and then they went into the music room to enjoy a wonderful musical event. The princess became "Tante Winnie" and it was an honor to maintain a level of excellence that her friends were invited to share, not for their social status or wealth, but for their talents or, more importantly, their love for music.

During World War I, Winnaretta began a project of commissioning works by young composers, such as Stravinsky, Poulenc, Satie, Falla, Milhaud, and Weill, among others.

Using the Singer Sewing Machine fortune to promote modern French music, she built up a repertoire of nearly twenty commissioned works, most of which had their first performances in her salons, and which are still in the active repertoire today.

Satie: La mort de Socrate (part I)

Winnaretta spent a part of every year in Venice, where she welcomed musicians from every corner of Europe. During her long stays during the summer and autumn months, she hosted musical gatherings that became as renowned as those held in her Paris salons. Pianists Clara Haskil and Renata Borgatti and violinist Olga Rudge (Ezra Pound's lover) performed there so frequently that they were practically "house musicians." Diaghilev and Cole Porter were regulars, as were members of Les Six. Arthur Rubinstein spent his honeymoon at the Palazzo Polignac. Toscanini was often in attendance at the musical gatherings; after the concerts, he would go to the kitchen to help prepare the spaghetti. Vladimir Horowitz lived there for a number of years, and he and Winnaretta became close friends.

Stravinsky in Venice

Winnaretta was also influential in making sure that the works of French composers whom she patronized were given places in the summer festivals.

She was the honorary president of the International Festival of Music of the 1932 Venice Biennale, and it was thus that Poulenc's Two-Piano Concerto and Falla's El Retablo de Maese Pedro were featured at the Festival. Stravinsky wrote Winnaretta a Piano Sonata as a "thank you" for her support, and that work, too, was premiered in Venice, in 1925.

Falla: El Retablo de Maese Pedro

Winnaretta and Igor Stravinsky on the balcony of Palazzo Contarini Polignac

Since Winnaretta was one of Venice’s more visible celebrities, this kind of anecdote became grist for the local gossip mill. Sometimes, however, the gossip had a sharper edge. It was reported that Winnaretta had invited to dinner a beautiful Englishwoman, for whom she had a soft spot, without the woman’s husband.

The uninvited spouse, upon learning of his wife’s whereabouts, arrived at the Palazzo Polignac in a heightened state of jealousy and inebriation. He pushed his way past the servants, entered the dining room, and delivered a furious challenge to his putative rival: “If you are the man you pretend to be, come and fight a duel tomorrow at the Lido!” He was eventually ushered from the room, but not before he had flung the place settings and candlesticks into the Grand Canal. These items were reportedly recovered the next day, but by then, the previous evening’s events had already circulated among the purveyors of gossip, providing entertaining material for mischievous tongues.

Legacy

If Winnaretta was the subject of gossip about her private life, it was because she was such an influential patron in public life. Her generosity as a supporter of composers and musicians represented only one small part of her patronage activities. She underwrote the literary activities of the French writers Paul Valéry, Anna de Noailles, and Colette, and, in the pre-World-War I years, created an “Edmond de Polignac Prize”, awarded annually to up-and-coming British writers. She supported the scientific work of Edouard Branly, developer of the “télégraphe sans fil”. During World War I she worked with Marie Curie to amass a fleet of the limousines belonging to her aristocratic friends and funded the conversion of these vehicles into ambulances that could be driven to the front. Winnaretta was especially active in the domain of public housing in Paris, before this kind of initiative became a concern of local and national governments. She first sponsored the construction of apartments for working-class families in the 13th arrondissement; these low-rent dwellings were equipped with modern appliances and plumbing, and were constructed with attention to light and safety features for children. In the 1920s and 1930s, Winnaretta joined forces with the French branch of the Salvation Army to build or reconstruct existing buildings as shelters for the homeless and for battered and abandoned women with children.

She commissioned modernist architect Le Corbusier – who was, at that point, the “black sheep” of French architecture – to undertake the designs and construction management of these complex projects. In 1928, Winnaretta established the

Winnaretta's hôtel particulier at the corner of the avenue Henri- Martin and the rue Cortambert in Paris

Fondation Singer-Polignac, whose goal was the promotion of music, the arts, science, and literature. During Winnaretta’s lifetime, the Fondation underwrote archeological digs in Greece and new equipment for Paris scientific laboratories. Today, the Fondation supports colloques on scientific and artistic subjects and features an outstanding series of concerts performed by young Artists-in-Residence. After Winnaretta’s death her estate donated a yacht – appropriately named the “Winnaretta Singer” -- to the Oceanographic Museum of Monaco; this vessel was used for research by Captain Cousteau.

Winnaretta Singer-Polignac was in England when World War II broke out in 1939. She never returned to Paris. She was active in England's musical life during the war years, and organized many charitable events that included the talents of her musician friends. Although she thought about emigrating to America, she could never find the courage to get on the airplane and leave her past behind. She died in London on 26 November 1943, in the midst of a fierce bombardment of the city. On the first anniversary of her death, Le Figaro published an article written in memory of the Princess de Polignac, regretting that her death a year earlier occurred during a period in which, "the events and the subjugation of free speech in France made it impossible to speak in a manner befitting the Princesse Edmond de Polignac and the homage she deserves. It is impossible to write the chronicle of the twentieth century without including the salon on Avenue Henri-Martin and the palazzo on the Grand Canal."

Winnaretta Singer, Princesse Edmond de Polignac was one of the most illustrious patrons of all time, and her influence, even to this day, is immeasurable.

Winnaretta Singer, yacht donated to the Oceanographic museum of Monaco

Les Dindons blancs by Claude Monet, acquired by Winnaretta

"Music's Modern Muse", Sylvia Kahan

http://www.urpress.com/store/viewItem.asp?idProduct=10505

http://www.boydellandbrewer.com/store/viewItem.asp?idProduct=10505

Portrait Gallery

Introduction

This portrait gallery is a project conceived and devised by the British author Robin Saikia. It is devoted principally to Winnaretta Singer's friends and family and to the many great musicians and composers who enjoyed her patronage. Robin Saikia writes: "Following Winnaretta's death in 1943, a great many articles were published celebrating her life and work. One, in Le Figaro, included the following comment: 'It is impossible to write a cultural history of the 20th century without mentioning the salon on the Avenue Henri Martin and the Palazzo on the Grand Canal.' Winnaretta's influence cannot be too greatly emphasised. Fauré, Poulenc, Satie, Stravinsky and many others benefited from her patronage. She counted Marcel Proust, Ezra Pound and Vladimir Horowitz among her many friends. She was a highly accomplished musician and painter, and a fearsome and astute businesswoman - rare and ideal qualities in a patron of the arts. This gallery, I hope, offers a few helpful snapshots of her circle. It will, no doubt, expand as time goes on." RS, Palazzo Contarini-Polignac, October 2015.

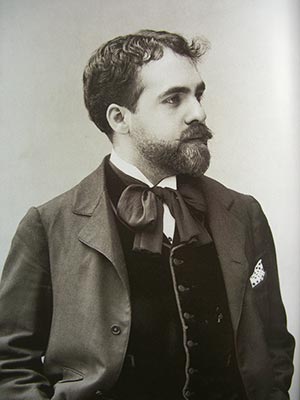

Isaac Merrit Singer

Winnaretta's father, Isaac, was one of the most colourful entrepreneurs on either side of the Atlantic during the mid-19th century. He made a considerable fortune from the design and manufacture of the iconic Singer sewing-machine. Born in Pittstown, New York, he ran away from home at the age of eleven to join a travelling theatre company. Even after his first commercial success, a machine for drilling into rock, he remained drawn to the stage and took his family on a five-year theatrical tour with his own company, the Merrit Players. He had 24 children (this is the official count, though there may have been more), many of whom were generously provided for after his death. Winnaretta inherited a fair share of her father's business acumen as well as his money. She took care of her considerable fortune, some 2 million dollars at the outset, and was one of the few rich Americans to emerge comparatively unscated from the economic setbacks of the Twenties.

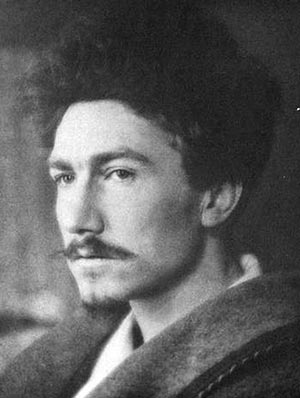

Prince Edmond de Polignac

Winnaretta's husband Edmond was born into one of the most distinguished families in France. His grandmother, the duchesse de Polignac, had been a close friend of Marie Antoinette. His father, Jules, had been a senior minister in the reign of Charles X. Following the overthrow of the Bourbon dynasty in 1830, Jules was tried for crimes against the state, largely because he had been the principal architect of the July Ordinances, which negated the Constitution and granted absolute power to the monarch. The family was exiled, and Jules was brought up in Bavaria thanks to his father's close association with the king, Ludwig I. He returned to Paris in the 1840s and studied music and composition at the Conservatoire under Napoléon Henri Reber. He was also a co-founder, in 1861, of the the Cercle de l'Union Artistique, a group of enlightened music lovers who, among other things, supported Wagner after the disastrous reception of Tannhäuser in 1861. Edmond was 57 when he met Winnaretta. Though respected as a musician and composer he was desperately broke, so much so that he had even been reduced to selling his furniture. Brought together by Robert de Montequiou-Fezensac, Edmond and Winnaretta soon became good friends. The marriage that followed - a mariage blanc, since they were both gay - was a perfect solution for both of them. His title firmly established Winnaretta as a member of European society. Her fortune solved all Edmond's longstanding financial problems once and for all. Their shared love of music brought the harmonious intellectual communion and companionship they had both previously lacked. Sadly, Edmond died in 1901, only a year after Winnaretta had bought the Palazzo Contarini. The rest of her life was, in the main, a celebration of Edmond, his love for music, and her love for him.

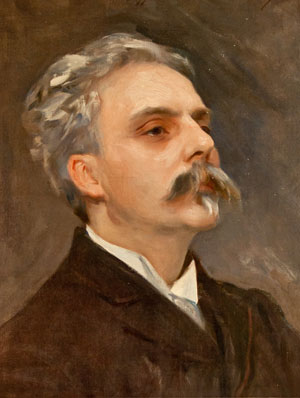

Gabriel Fauré

Fauré was one of Winnaretta's oldest and most loyal friends. They first met in Paris in 1880 - when Winnaretta was still only 15 - and remained close friends until the composer's death in 1924. Their first collaboration got off to a rocky start in 1890 when Winnaretta decided to commission an opera with music by Fauré and a libretto by Paul Verlaine, whose work Winnaretta greatly admired. However, neither of them had bargained for Verlaine's legendary alcoholism and unreliability. By the summer of 1891 Verlaine had produced nothing and Fauré was at his wits end. He and Winnaretta spent the summer in Venice where she had rented a palace - and during this welcome break from Paris he began work on the Opus 58 song cycle, Cinq Melodies de Venise. Fauré was organist at Edmond de Polignac's funeral in Paris in 1901. Later, in 1905, he was appointed Vice-President of the Edmond de Polignac Foundation, set up by Winnaretta in her husband's memory. Shortly before Fauré died, he wrote Winnaretta a touching valediction: "...I so often think of the marvellous times in Paris or in Venice that I owe to you, the only Winnie in the world!"

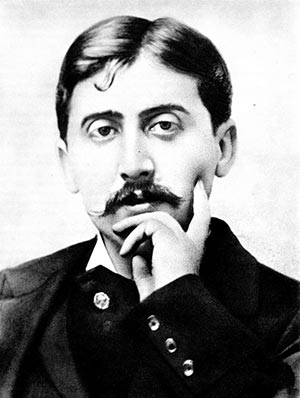

Marcel Proust and Reynaldo Hahn

Marcel Proust and the Venezuelan-born composer Reynaldo Hahn were lifelong friends and, for a brief spell, lovers. Winnaretta first encountered Proust and Hahn in Paris in the 1890s where Hahn gave regular recitals at the salon of Madeleine Lemaire. Proust meanwhile, a newcomer in Paris society, had joined the entourage of the flamboyant aesthete Comte Robert de Montesquiou. The two soon became regular guests at Winnaretta's salon in Avenue Henri-Martin. In 1900 they joined the Polignacs on the decisive trip to Venice that ended in Winnaretta's purchase of the Palazzo Contarini as a gift for her husband, Edmond de Polignac. Winnaretta had recently acquired a portable 'yacht piano', still in use at the palazzo today. This was installed in a gondola and Hahn memorably entertained the company on the Grand Canal with moonlit recitals of his songs. Hahn, an ardent melodist and a resolute Mozartian, was no lover of the avant garde, but he nevertheless became and remained a close friend of Winnaretta Singer.

Cole Porter and Darius Milhaud

At first sight this may seem an unlikely pairing, but it serves to illustrate how a chance meeting in an effective salon can trigger startling creative results. Winnaretta first met Darius Milhaud in Paris in 1913. She was sitting for a portrait by Jacques-Emile Blanche, who used to entertain his sitters and their friends with musical recitals in his studio, often of new music by young composers. Among his proteges was Darius Milhaud, then a twenty-year-old newcomer from the depths of Provence. One day, during a break in her sitting, Winnaretta found herself standing in as page-turner while Yvonne Giraud and Georgette Guller performed Milhaud's Violin Sonata. She was impressed by Milhaud and some years later commissioned him to write an opera, Les Malheurs d'Orphee. He soon became a welcome guest in Venice. By the 1920s Cole Porter and his wife Linda were regular and very visible visitors in Venice. In 1923 Porter rented the Ca'Rezzonico on the Grand Canal, the former home of Robert Browning. There he gave a series of breathtakingly extravagant and noisy parties, often retaining no fewer than 150 gondoliers as waiters and footmen. There were quieter gatherings too, comparatively sedate dinner parties for an inner circle of friends including Diaghilev, Serge Lifar, Vittorio Rieti, Boris Kochno and the Polignacs. The Porters soon became regular guests at the Palazzo Contarini Polignac and it was there that Cole Porter met Darius Milhaud. They got on well and Milhaud introduced Porter to Rolf Mare, the director of the Ballet Suedois. Mare subsequently commissioned Porter's only ballet, Within the Quota, a lively satire of American life in the "roaring twenties".

Click to read more

Esra Pound and Olga Rudge

Rudge Ezra Pound and his lover Olga Rudge were among the more colourful regular guests at Palazzo Contarini Polignac. Winnaretta turned a blind eye to Pound's fascist tendencies and their friendship was based largely on a mutual love of music. Olga Rudge was an accomplished violinist and soon became one of the 'house' musicians at the palace, either giving concerts or participating, along with other artists, in Winnaretta's enthusiastic read-throughs of the piano trio and quintet repertoire.

Winnaretta Singer and Antonio Vivaldi

In many ways this may seem an even unliklier pairing than that of Cole Porter with Darius Milhaud, but it is true to say that Winnaretta played a great part in the revival of many of Vivaldi's best-loved works, largely thanks to her friend Olga Rudge. While researching early music in Dresden, Rudge came across a substantial collection of Vivaldi manuscripts, mostly of violin concerti. She transcribed the manuscripts - an enormous task - and brought her work back to Venice where, with Winnaretta's support, she and Ezra Pound began preparing their Vivaldi discovery for publication. Today, Vivaldi is an enormously popular composer, but in the early 20th century he was known mainly only by connoisseurs. Many of the pieces discovered by Rudge had not been played in public for over two centuries - and Winnaretta began to intersperse her modern programs with examples of the concerti from Dresden.

Francois Poulenc and Manuel de Falla

Poulenc's 2nd piano concerto and Manuel De Falla's opera Retablo were both commissioned by Winnaretta. One of the many pleasing vignettes of life at Palazzo Contarini Polignac is of the two musicians staying at the palace in the summer of 192x. Days were spent playing a quatre mains in the music rooms, but in the evening the two would part company. The shy De Falla would go for long walks and visit churches. The decidedly more bohemian Poulenc would walk the streets in search of romantic encounters with young men.

Daisy Fellowes

Daisy Fellowes was Winnaretta's niece and following her mother's death came to live with her aunt in Paris and Venice. She was a shy, awkward and ungainly girl at the outset, but soon blossomed into one of the most celebrated society figures in Europe. She was photographed by Cecil Beaton wearing frocks by prominent new designers including Chanel, Lanvin and Balenciaga. Her style was chic, simple and uncluttered - Chanel was her favourite designer - and for a time she very nearly singlehandedly redefined the concept of chic, abandoning the fussiness and theatricality of the Belle Époque in favour of bold designs, plain colours and simple lines. Her taste in jewellery was revolutionary too. Cartier made several pieces to her exacting designs, which played a great part in redefining the Cartier house style.

Vladimir Horowitz

Horovitz was well known as a flamboyant and energetic pianist early on in his career. He was also an affable and prominent socialite on both sides of the Atlantic. All that changed, for a time, following his marriage to Wanda Toscanini, daughter of the celebrated conductor. His wife, no doubt with the best intentions, was fiercely protective, rationing his appearances on the social circuit and keeping his thousands of fans at arm's length. The strain of the new arrangement proved too much for Horovitz, who retired from the concert platform following a nervous breakdown. During his self-imposed sabbatical, he would come to Venice and spend time with Winnaretta at the palazzo. Relaxing walks on the Lido and dinners with close friends formed part of the 'remedy' prescribed by Winnaretta. It paid off, and by 1935 Horovitz had returned to the concert platform, fully revitalized.

Comte Robert de Montesquiou-Fezensac

Montesquiou was a prominent dandy and aesthete in Paris during the 1880s and 90s. He is remembered largely today as the model for Proust's Baron Charlus and for Joris-Karl Huysmans' neurotic aesthete, Des Esseintes. He was the principal architect of Winnaretta's marriage to Prince Edmond de Polignac. 'Mauve' marriages - marriages between lesbians and gay men - were not unusual in upper-class society at the time, but Montesquiou's matching of Winnaretta was nothing short of a masterpiece. By bringing them together he satisfied two of Edmond's most pressing needs, the need for a kindred spirit - preferably one with an intense love of music - and the pressing need for hard cash. Sadly, following their marriage, he fell out with Winnaretta and Edmond because (he maintained) he had not been invited to the wedding. Though Edmond strenuously denied this, Montesquiou was implacable. From then on he took every opportunity to make cutting remarks about Winnaretta's 'nouveau riche' background.

Coco Chanel

By 1923, the designer Coco Chanel had become the mistress of the Duke of Westminster and regularly toured the Mediterranean in his yacht. Venice was a favourite destination. While the duke provided an introduction to high society, her friend Misia Sert had introduced her to the the world of avant-garde culture. She met and befriended Diaghilev and, like Winnaretta, became a staunch supporter of the Ballets Russes. During one of his many attempts to extract funds from his rich patrons, Diaghilev told Chanel that although Winnaretta had given him 75,000 francs, he and the company were still broke. Chanel reached for her chequebook, making the following decidedly acid remark. “The Princesse do Polignac is a grand American lady, I am only a seamstress. Here is 200,000.” Chanel remained loyal to Diaghilev to the end. When he died at the Hotel des Bains on the Venice Lido, she paid for his funeral and settled his long-overdue bill at the hotel.

Marie-Blanche de Polignac

Marie-Blanche, Winnaretta's niece by marriage, was the only daughter of the celebrated designer Jeanne Lanvin and her Italian husband Count Emilio di Pietro. Christened Marguerite, she preferred to be known as Marie-Blanche following her marriage to Count Jean de Polignac. Though she eventually played an active role at Lanvin following her mother's death, music remained her first love. She was an accomplished pianist and a highly regarded soprano. She often found herself sight-reading difficult four-handed piano scores with her aunt during musical evenings at the Palazzo Contarini-Polignac. As a soprano, she gave wonderful accounts of Monteverdi's madrigals, directed by her friend and mentor, the pianist Nadia Boulanger.

Richard Wagner

Among the many fascinating objects in the Palazzo Contarini-Polignac collection is a wonderful portrait of Wagner by the Belgian painter Henry de Groux, illustrated here. There is also a splendid pair of sofas that formerly belonged to Wagner and were rescued by Winnaretta from the composer's home in Venice, the Palazzo Vendramin Calergi. Edmond and Winnaretta shared a great passion for Wagner. Following Edmond's death, Winnaretta set aside a fund to sponsor an annual Wagner concert in his memory. The inaugural event took place in the campo outside the Palazzo Vendramin Calergi and featured excerpts from Wagner's operas, including the funeral march from Götterdämmerung.

Winnaretta and Marcel Proust

By an unkind stroke of fate, the many letters exchanged by Winnaretta and Marcel Proust have been lost. Winnaretta and Edmond were introduced to Proust in 1894 in Paris, by Count Robert de Montesquiou-Fezensac.Proust soon became a regular guest, along with his friend Reynaldo Hahn, at the Polignac salon in Paris, where he heard many of the great composers and performers of the day including Charles-Marie Widor, Eugène Gigout, Louis Vierne, Alexandre Guilmant and Gabriel Fauré. In 1900 Proust and Hahn visited Venice with the Polignacs, during the memorable trip in which Winnaretta decided to buy the Palazzo Contarinni-Polignac as a gift for Edmond. Proust embraced the city - "When I came to Venice I found that my dream had become, quite incrdibly but simply, my address...". He remains one of the most compelling expatriate writers on Venice. The Venetian passages in Albertine Disparue are strikingly orginal, often comparing and contrasting the very difficult worlds of Venice and Combray to great effect.

Igor Stravinsky and Serge Diaghilev

Stravinsky and Diaghilev both benefited enormously from Winnaretta's generous (and, in Diaghilev's case, often very tolerant) patronage. Diaghilev, though an energetic impresario, had a very sketchy grasp of budgets and balance sheets. The Ballets Russes, as many of its supporters found to their cost, was a bottomless pit capable of emptying even the deepest pockets. Nevertheless, despite his fecklessness, Diaghliev was a fearless impresario - and produced the first performance of Stravinsky's controversial work, Le Sacre du Printemps, in 1913. Eventually Winnaretta chose to maintain her relationship with Stravinsky but to distance herself from Diaghilev. She persuaded her nephew, Prince Pierre of Monaco, to take her place as principal patron of Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes. Meanwhile, she gave Stravinsky a series of commissions beginning, in 1915, with Renard, a burlesque opera-ballet based on a collection of folk tales collected by Alexander Afanasysev. Stravinsky loved Venice and was a regular guest at Palazzo Contarini-Polignac. He left instructions that he should be buried in Venice, in the Russian corner of the city's cemetery, San Michele, also the final resting palce of his erswhile collaborator, Diaghilev.

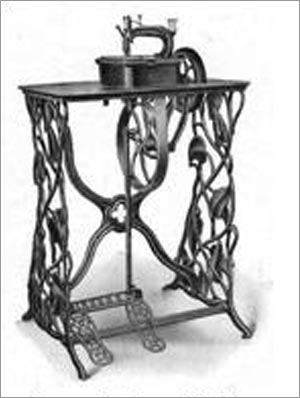

Isaac singer

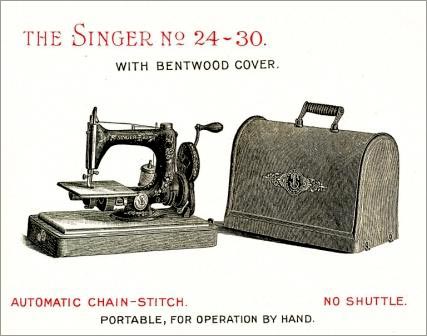

Isaac was a colourful character who started life as an itinerant mechanic. He was also an itinerant actor-manager and had founded his own repertory company - a startling combination of practical skills and creative inclination. His first great technological breakthrough came in 1839, when he patented a simple but very effective horse-powered rock-drilling machine, a project he developed while working with his brother on the construction of canal networks in Chicago. He earned $2000 dollars from the patent which he promptly invested in his theatrical company - but although the company built up an impressive Shakespearian repertoire it ended up broke, in Ohio, in the mid 1840s. Undeterred by these setbacks, Singer went to work in a print shop in Fredericksburg where he developed an intricate machine for carving images and typefaces in wood and and metal. Bad luck struck again however - and in 1849 the only production model of his typesetting machine was destroyed in a factory explosion. Showing characteristic resilience Singer set about building his machine from scratch, renting a workshop in the premises of Orson C Phelps, an machinist and entrepreneur based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. This new chapter - marked by a close collaboration between Singer and Phelps - saw the birth of the Singer sewing machine.

Phelps's principal business was the manufacture and repair of a sewing machine patented by Lerow and Blodgett This machine was satisfactory as far as it went, but was slow and in constant need of maintenance. Singer applied his skills to the improvement of the Lerow and Blodgett model and following a series of successful innovations he finally patented his own machine. It was dramatically different from previous models in many respects. To begin with, it was built on a solid iron frame which made it considerably more stable than its predecessors. Then, the greater stability resulted in phenomenally increased production power. Not only was this new machine a hit in the domestic market. It soon became clear that it could have a huge impact on the wholesale garment manufacturing industry. There was a key 'eureka' moment during the initial design of the machine. Phelps had advanced the penniless Singer $40 to build a prototype of a new and improved mechanism. After 11 days of work (as Singer himself put it, "sleeping but three or four hours a day"), the new model was ready: but it would not work. On the way home, despondent after a botched demonstration, Singer suddenly realized that he had forgotten to adjust the tension on the thread. A quick tweak in the early hours of the morning resulted in a perfect performance - and in the birth of one of America's first major corporations. Singer is famously quoted as saying "I don't care a damn for the invention. The dimes are what I'm after." This is pleasing braggadocio in the wake of his success, but it seems clear from the early chapters of his life - the hard work, the resilience in the face of misfortune - that he was rather more than a mere opportunist in the classic American boom or bust mode.

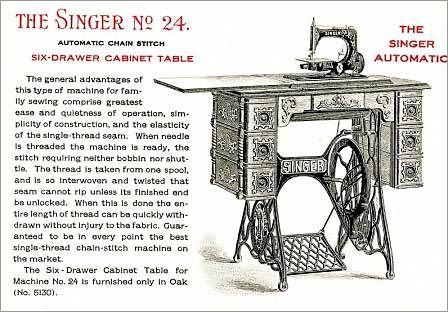

To form an impression of the scale of Singer's success, one must look at the financial position of the company in 1890, a mere three decades after the initial investment of $40. By 1890 the company had cash reserves of $12.8 million dollars, a further cash surplus of $14.5 million and accounts receivable of some $20 million. These figures added together - and translated into today's purchasing power - amount to a corporate net worth of nearly a billion dollars. The company rapidly expanded and one of the great success stories was the opening of a factory in Glasgow, Scotland. The demand for the machines so far outstripped the supply that the corporation was forced to build a further six floors onto the premises in order to cope with production. The corporation also did its bit for the war effort in both the first and second world wars, applying its formidable production line to the development and manufacture of ordnance and the stitching of gunpowder bags. The corporation consistently rose to the challenges presented by new materials such as nylon, rubber and other man made fabrics. Significantly, during the worst years of the depression, the Singer company was one of the few entities to weather the storm, declaring an 8% dividend on its shares in 1932.

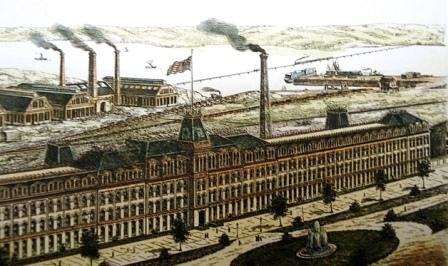

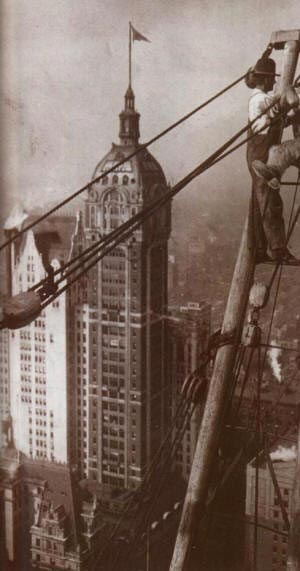

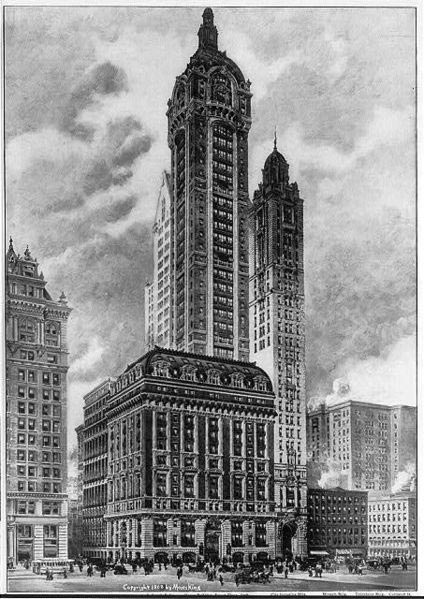

The Singer Building in New York was constructed from September 1906 to May 1908 becoming the tallest building in the world, and headquarters of Singer company. It is also thallest building ever to be demolished by a company

PetersbourgOn St. Petersburg's main street, Nevsky Prospekt, is the Singer building, once the sewing machine company's Russian headquarters