Isaac Singer

Winnaretta's father, Isaac, was one of the most colourful entrepreneurs on either side of the Atlantic during the mid-19th century. He made a considerable fortune from the design and manufacture of the iconic Singer sewing-machine. Born in Pittstown, New York, he ran away from home at the age of eleven to join a travelling theatre company.

Even after his first commercial success, a machine for drilling into rock, he remained drawn to the stage and took his family on a five-year theatrical tour with his own company, the Merrit Players. He had 24 children (this is the official count, though there may have been more), many of whom were generously provided for after his death. Winnaretta inherited a fair share of her father's business acumen as well as his money. She took care of her considerable fortune, some 2 million dollars at the outset, and was one of the few rich Americans to emerge comparatively unscated from the economic setbacks of the Twenties.

Singer Sewing Machine Company SSMC

First conglomarate entreprise in the world established in 1851

- 5000 branch offices and sewing centers, 190 countries ( political entities ). From South American jungles to Indian deserts

- Branch offices in 1880 not only in Euroupe but Australia, New Zealand, Brazil, India,China, Canada, Carribean, Philippines , Japan. Sold in Tibet, South America, Indo China by 1912

- Translated its sewing machine instructions and repair manuals into at least 54 languages

- 3000 machines explained in a 380 page catalogue

- For a century, it owned all of its branch offices and factories outright , including the real estate

- First company in the world for more than 1 million $ marketing budget after WW II, in 15 production facilities

- More than 100 year of predictable profitability, without giving out sales or productino figures

- Securities and Exchange Comission for stock market crime and fraud forced the Singer company to bankruptcy in 1989

- Had it maintained its 100 year old policies , it could today be the greatest conglomerate on earth

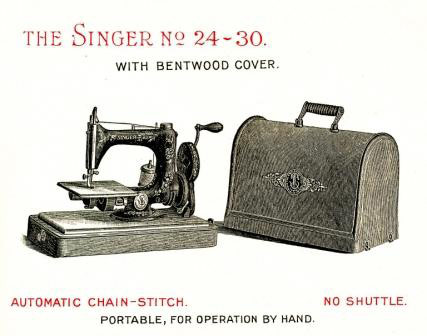

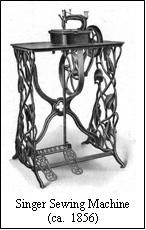

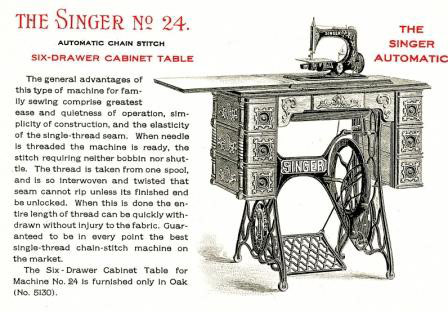

Singer Sewing Machine

1853 Sewing

Winnaretta Singer is acknowledged to be one of 20th century’s greatest and most discerning patrons of the arts, in particular of music. She is also remembered as a signi cant philanthropist both in France and in her native USA. In Venice she is notable for having bought the Palazzo Contarini Polignac as a gift for her husband, Prince Edmond de Polignac. The palazzo is to this day a thriving cultural centre. None of this could have been created or sustained were it not for the vision and energy of her father, Isaac Merritt Singer, founder of the Singer Sewing Machine Company. Of her many siblings, most of whom were generously provided for in Isaac’s will, Winnaretta was perhaps the most shrewd and imaginative steward of her considerable inheritance.

Isaac was a colourful character who started life as an itinerant mechanic. He was also an itinerant actor-manager and had founded his own repertory company - a startling combination of practical skills and creative inclinations. His rst great technological breakthrough came in 1839, when he patented a simple but very effective horse- powered rock-drilling machine, a project he developed while working with his brother on the construction of canal networks in Chicago. He earned $2000 dollars from the patent which he promptly invested in his theatrical company - but although the company built up an impressive Shakespearian repertoire it ended up broke, in Ohio, in the mid 1840s. Undeterred by these setbacks, Singer went to work in a print shop in Fredericksburg where he developed an intricate machine for carving images and typefaces in wood and and metal. Bad luck struck again however - and in 1849 the only production model of his typesetting machine was destroyed in a factory explosion. Showing characteristic resilience Singer set about building his machine from scratch, renting a workshop in the premises of Orson C Phelps, an machinist and entrepreneur based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. This new chapter - marked by a close collaboration between Singer and Phelps - saw the birth of the Singer sewing machine.

Phelps's principal business was the manufacture and repair of a sewing machine patented by Lerow and Blodgett. This machine was satisfactory as far as it went, but was slow and in constant need of maintenance. Singer applied his skills to the improvement of the Lerow and Blodgett model and following a series of successful innovations he nally patented his own machine. It was dramatically different from previous models in many respects. To begin with, it was built on a solid iron frame which made it considerably more stable than its predecessors. Then, the greater stability resulted in phenomenally increased production power. Not only was this new machine a hit in the domestic market. It soon became clear that it could have a huge impact on the wholesale garment manufacturing industry. There was a key ‘eureka’ moment during the initial design of the machine.

Phelps had advanced the penniless Singer $40 to build a prototype of a new and improved mechanism. After 11 days of work (as Singer himself put it, “sleeping but three or four hours a day”), the new model was ready: but it would not work. On the way home, despondent after a botched demonstration, Singer suddenly realized that he had forgotten to adjust the tension on the thread. A quick tweak in the early hours of the morning resulted in a perfect performance - and in the birth of one of America’s rst major corporations. Singer is famously quoted as saying “I don’t care a damn for the invention. The dimes are what I’m after.” This is pleasing braggadocio in the wake of his success, but it seems clear from the early chapters of his life - the hard work, the resilience in the face of misfortune - that he was rather more than a mere opportunist in the classic American boom or bust mode.

To form an impression of the scale of Singer’s success, one must look at the nancial position of the company in 1890, a mere three decades after the initial investment of $40. By 1890 the company had cash reserves of $12.8 million dollars, a further cash surplus of $14.5 million and accounts receivable of some $20 million. These gures added together - and translated into today’s purchasing power - amount to a corporate net worth of nearly a billion dollars. The company rapidly expanded and one of the great success stories was the opening of a factory in Glasgow, Scotland. The demand for the machines so far outstripped the supply that the corporation was forced to build a further six oors onto the premises in order to cope with production.

The corporation also did its bit for the war effort in both the rst and second world wars, applying its formidable production line to the development and manufacture of ordnance and the stitching of gunpowder bags. The corporation consistently rose to the challenges presented by new materials such as nylon, rubber and other man made fabrics. Signi cantly, during the worst years of the depression, the Singer company was one of the few entities to weather the storm, declaring an 8% dividend on its shares in 1932.

A considerable portion of this wealth was inherited by Winnaretta, who ltered it into both the arts and philanthropy in a way of which her father would certainly have approved. In addition to her patronage of major composers like Stravinsky, Poulenc, Satie and Fauré, she was actively involved in charitable work. Notable schemes include a major public housing scheme in Paris overseen by Le Corbusier, and the Foch Hospital in Suresnes. Her and her father Isaac’s story is an encouraging example of how the fruits of commercial success can be channeled into creative enterprise - and Winnaretta’s spirited approach remains embodied in the activities of the Fondation Singer Polignac to this day.

From "The First Conglomerate- 145 Years of the Singer Sewing Machine Company", by Don Bissell

Singer Building 1908

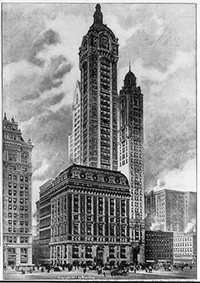

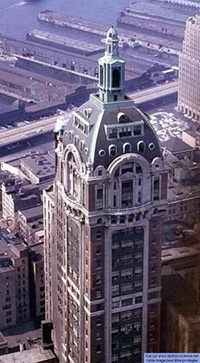

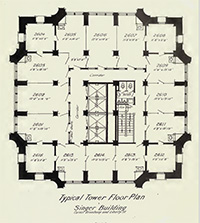

The Singer Building (1906-1908) Demolished in 1968Location : Broadway and Liberty Street

Use: corporate headquarters.

Location: Broadway, New York, USA.

Architect: Ernest Flagg, assisted by George W. Conable.

Client: Frederick Bourne, for the Singer Sewing Machine Company.

Style: Beaux-Art, Second Empire Baroque

Ambitious project

- the one that the visitor to New York will go to see on his first day in town

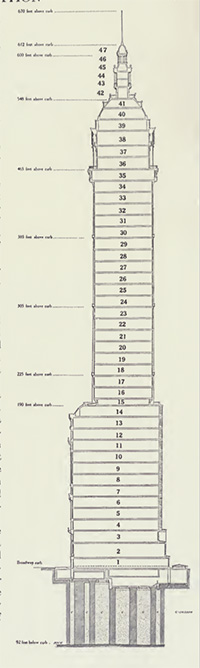

- It will be 36 stories high 25 of it will rise up like a tower,

- almost as high in itself as the Washington Monument,

- from a fundamental building of eleven stories in height

- no exposed woodwork throughout the building.

- Steel frame , lime stone trim, red brick

- It's cost will be $1,500,000.

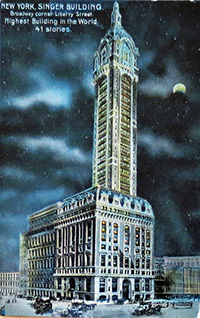

The rush was on to build taller and costlier office buildings. On July 22, 1906 the New-York Daily Tribune wrote of the $75 million worth of new buildings going up in Downtown—including the soaring Singer Building. In an article titled "Vast Sums, Vast Piles" it singled out the planned structure. "The Singer Building is to be the one that the visitor to New York will go to see on his first day in town…[It] will be thirty-six stories high, but what will make it yet more remarkable is the fact that twenty-five of these stories will rise up like a tower, almost as high in itself as the Washington Monument, from a fundamental building of eleven stories in height….The architect, Ernest Flagg, says that there will be no exposed woodwork throughout the building. Its cost will be $1,500,000."

World tallest building for 17 months

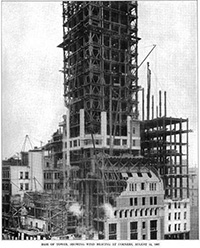

Construction 1906-1908

1907, plans had changed and an additional 5 floors were added to the height.

"The tower of the Singer Building will have 41 floors containing offices, and will be 13 stories higher than any other structure now standing in the city" said the New-York Tribune.

Construction would take two years to complete and New Yorkers followed the progress with riveted interest. By January 2, 1907, as the skeleton rose, plans had changed and an additional five floors were added to the height. “The tower of the Singer Building will have forty-one floors containing offices, and will be thirteen stories higher than any other structure now standing in the city,” said the New-York Tribune.

47 stories skyescraper

In addition, there was a 6-story lantern surmounting the tower.

upper 3 of these stories were housed under a mansard roof.

generally considered to be 41 stories

14 storie "base"

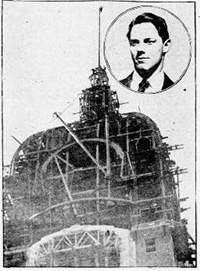

Gold leaf in the sky

"The highest point above the sidewalk ever attained by a man outside of a balloon (612 feet (186,5 m) from the pavement) in New York was reached yesterday by Ernest Capelle, steeplejack, who placed the golden ball on the top of the flagpole that surmounts the Singer Building in lower Broadway,"

reported the New-York Tribune on October 11, 1907

Having affixed the ball onto the flagpole, Capelle then had to gold leaf it.

Less than two months later crowds on the sidewalk below gazed in amazement as not a Swede, but an Italian, was raised 612 feet from the pavement to install the ball on the top of the flagpole. “The highest point above the sidewalk ever attained by a man outside of a balloon in New York was reached yesterday by Ernest Capelle, steeplejack, who placed the golden ball on the top of the flagpole that surmounts the Singer Building in lower Broadway,” reported the New-York Tribune on October 11, 1907 Having affixed the ball onto the flagpole, Capelle then had to gold leaf it. “With the ball once in place, the crowd saw him puttering about the top as he lay back in the rope sling that held him. He was putting the gold leaf on the ball, but this was not evident until he had finished and slipped down a few feet.”

The vision of Ernest Flagg

The Singer Building at 149 Broadway held the record, however briefly, as the tallest skyscraper in the world.

Sixty years later, it had the honor of setting a more enduring record – as the world’s largest skyscraper ever to be peacefully demolished.

The 612-foot-tall, 47-story headquarters of the Singer Sewing Machine Company had been a landmark of downtown Manhattan for decades, thanks in part to its unique shape.

The building’s architect, Ernest Flagg, deplored the way the sides of modern skyscrapers grew upward from the very edge of their plots, making narrow ravines of the city streets below.

He believed buildings more than 10 or 15 stories high should be set back from the street. It was a belief literally set in stone in the Singer Building’s most unique feature — a narrow 35-story tower that protruded from the structure’s lower floors.

When it was opened to the public in 1908, the Singer Building at 149 Broadway held the record, however briefly, as the tallest skyscraper in the world. Sixty years later, it had the honor of setting a more enduring record – as the world’s largest skyscraper ever to be peacefully demolished.

The 612-foot-tall, 47-story headquarters of the Singer Sewing Machine Company had been a landmark of downtown Manhattan for decades, thanks in part to its unique shape. The building’s architect, Ernest Flagg, deplored the way the sides of modern skyscrapers grew upward from the very edge of their plots, making narrow ravines of the city streets below. Mr. Flagg believed buildings more than 10 or 15 stories high should be set back from the street. It was a belief literally set in stone in the Singer Building’s most unique feature — a narrow 35-story tower that protruded from the structure’s lower floors.

Steel Structure

The buildings structure was structural steel, fireproofed by a covering of terra cotta hollow tile.

The mansard roof surmounting the first fourteen stories was covered with copper.

In the tower the sloping sides of the mansard roof were covered with Maine roof slate shingles.

The buildings structure was structural steel, fireproofed by a covering of terra cotta hollow tile. The exterior walls were constructed of rusticated North River blue stone on the first 3 stories. The upper stories were dark red brick laid up in English bond. A three-story, semi-circular arch, with a cartouche engraved with "Singer" in the keystone position of the architrave, formed the main entrance on Broadway. In the upper part of this arch was a fanlight with five vertical millions and below is a bronze grille, approximately thirteen feet wide and twenty-four feet high framed by a two-story architrave in the shape of a segmental arch. The grille consisted of a bar and scroll design and held a clock with two cupids supporting the Singer medallion. The two original revolving doors were replaced by three hinged doors. The mansard roof surmounting the first fourteen stories was covered with copper. In the tower the sloping sides of the mansard roof were covered with Maine roof slate shingles. The main entrance of the east facade opened into the large lobby with a stairway on the west wall leading up to a balcony which provided access to the banking rooms on the first floor. Staircases on each side of this lead down to the basement where safety deposit boxes were located. Another stairway, immediately to the right of the main entrance, also lead up to the banking room. A row of eight elevators formed the north wall of the center section of the lobby. The lobby was richly ornamented. There were two rows of eight piers, extending for the length of the lobby from the revolving doors to the west stairway. These piers were faced with Pavonazzo marble in a frame of grey Montarenti Sienna marble with corners covered with beaded bronze. At the top of each side of each pier was a bronze molding and medallion with the Singer Manufacturing Company's trademark. The pilasters along the walls of the lobby were decorated similarly. An arch springs from each side of these piers. Their intrados were decorated with ornamental plaster work of rosettes. The pendentives and drums of these bays were of richly ornamented plaster. A modern glass lighting fixture in the center of each drum replaced a flat, circular amber glass light set in a steel frame. Along the south wall were two marble staircases leading to the original Singer Building; on the west wall a marble staircase that divides them leads to the balcony. Both had bronze railings. On the landing of the staircase on the south wall there was a bronze-cased master clock. On the central portion of the north wall was a bank of eight elevators. Originally the doors and frames of these elevators consisted of bronze rosettes set in panels; they were replaced by modern doors.

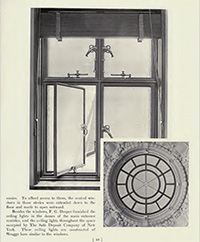

Iron Railing and Balconies

At every 7th story, on all four sides of the tower, were cast iron balconies supported by ornamental wrought iron brackets.

The window openings were graced with ornamental iron railings with French scrolled designs.

Architectural Giraffe

The Singer Building was the first in New York to be dramatically lit at night. This postcard's boast "Highest building in the world" would last only 18 months.

Not everyone loved the building. The New York Globe scoffed "For anyone but an eagle, the occupancy of a perch over 600 feet up is a matter of sentiment rather than reason, and until there is a balloon fire-rescue service established, there ought to be some limit to our real estate owners’ appropriation of the skies."

The newspaper called it an "architectural giraffe."

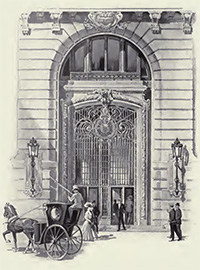

Entrance Doorway

A three-story, semi-circular arch, formed the main entrance on Broadway.

In the upper part of this arch was a fanlight with five vertical millions and below is a bronze grille, approximately thirteen feet wide and twenty-four feet high 7 m framed by a two-story architrave in the shape of a segmental arch.

The grille consisted of a bar and scroll design and held a clock with two cupids supporting the Singer medallion. The two original revolving doors were replaced by three hinged doors.

A three-story, semi-circular arch, with a cartouche engraved with "Singer" in the keystone position of the architrave, formed the main entrance on Broadway.

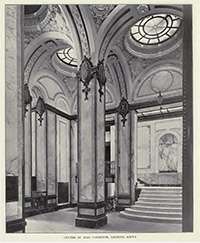

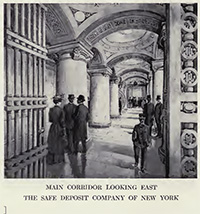

Lobby

The lobby was richly ornamented. There were two rows of eight piers, extending for the length of the lobby from the revolving doors to the west stairway.

These piers were faced with Pavonazzo marble in a frame of grey Montarenti Sienna marble with corners covered with beaded bronze.

The main entrance of the east facade opened into the large lobby with a stairway on the west wall leading up to a balcony which provided access to the banking rooms on the first floor.

Staircases on each side of this lead down to the basement where safety deposit boxes were located. Another stairway, immediately to the right of the main entrance, also lead up to the banking room.

The Singer Medallion

At the top of each side of each pier was a bronze molding and medallion with the Singer Manufacturing Company's trademark.

With a thread and needle

Arch Springs from Each Side of the Piers

The pilasters along the walls of the lobby were decorated similarly.

An arch springs from each side of these piers. Their intrados were decorated with ornamental plaster work of rosettes.

Lobby Ceiling

The lobby ceiling was a masterpiece of plasterwork. The "skylights" in the domes were electrically lighted.

A modern glass lighting fixture in the center of each drum replaced a flat, circular amber glass light set in a steel frame.

Gold Leaf Work

Gold leaf on the vaults and dome surmounting the columns .

Especially at night when the corridor remained illuminated while the rest of the building In is darkness , looked like the nave of a golden cathedral

The pendentives and drums of these bays were of richly ornamented plaster.

Bronze Master Clock

At the end of the hall is the bronze-cased Master Clock that regulated all the "secondary clocks" throughout the building

"Secondary clocks" were installed throughout the building and were actuated by the master clock in the lobby.

The master clock was wound daily by an electric motor that was powered by the electric plant in the building.

"The magneto apparatus is released every half minute, thus generating a positive and strong current, and operating the secondary clocks throughout the building,” explained Otto Semsch in his “A History of the Singer Building Construction."

Bronze Railings

Along the south wall were two marble staircases leading to the original Singer Building; on the west wall a marble staircase that divides them leads to the balcony. Both had bronze railings.

Executive Offices

The executive offices of the Singer company covered the entire 34th floor.

Here were Oriental rugs, custom-designed Empire-inspired mahogany furniture and carved woodwork.

Semsch commented "Such furniture appeals to the discriminating man and creates the right impression upon all who see it."

Ultra Modern Convenience

Meanwhile, upstairs, tenants enjoyed ultra-modern conveniences.

There was a central, building-wide vacuum system, a refrigerating plant for the cooling of the drinking water (which was filtered), and an amazing electric clock system.

38 Tons of Ornamental Bronze

Inside, the marble columns and walls were embellished with more than 3,600 lineal feet of cast bronze molding plus 80 bronze medallions bearing the trademark of the Singer Manufacturing Company.

stair railings,

interior balconies,

office doors

the master-clock on the main stairs in the lobby

were all of bronze.

Thirty-eight tons of ornamental bronze were used

A row of eight elevators formed the north wall of the center section of the lobby.

The elevator doors,

were all of bronze. Thirty-eight tons of ornamental bronze were used

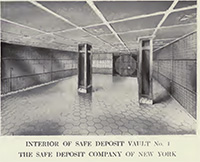

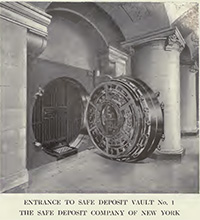

Safety Deposit Company in the Basement

The Safe Deposit Company of New York took about 10,000 square feet in the basement of the new building, signing a 20 year lease. The term "basement" however, was misleading. Ornate columns and arched vaults upheld a series of domes in the cathedral-like space. The specially-designed and constructed level "offers its patrons the most secure, elaborate and convenient means for the safe keeping of valuables."

In 1961, Singer Sewing Machine Corporation decided to move uptown and out of the building because it had become "obsolete."5 The property was bought by the development firm of Webb & Knapp.6 Webb & Knapp also purchased the City Investing Building, the only other building on the block, in hopes of relocating the New York Stock Exchange to the site.7 Meanwhile, future executive director of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) Alan Burnham classified the Singer Building as having historical significance in his 1963 inventory of “New York Landmarks.”8 However, it was recognized by Burnham that it would be virtually impossible for the LPC to save the building. According to Burnham, “if the building were made a landmark, we would have to find a buyer for it or the city would have to acquire it. The city is not wealthy and the commission doesn’t have a big enough staff to be a real-estate broker for a skyscraper.”9 United States Steel purchased the site in 1964 after the attempts to relocate the New York Stock Exchange failed. United States Steel intended to build a new 54-story building in place of the Singer Building and the City Investing Building, which later became known as One Liberty Plaza.10 Finally, in 1967, the Singer Building was demolished, making it the largest building ever to be demolished. While the Singer Building was quickly surpassed as being the world’s tallest building, it remains the world’s largest structure to be intentionally demolished.11 When it became clear that the demolition was inevitable, there were many who then fought to save the lobby of the building. However, the City approved demolition of the entire building regardless. The only piece of the building which remains today are chandeliers from the lobby, which were salvaged and installed in the East Building at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn.12 The loss of the structure has been described as the “city’s greatest loss since Penn Station” by the AIA Guide to New York City.13

Demolition

In 1961, the Singer Company announced plans to move its headquarters north to Midtown.

Webb & Knapp, bought the Singer tower and the rest of the block, hoping to get the New York Stock Exchange to relocate there.

Unable to generate corporate interest in the space because the small square footage of the building’s narrow tower was antithetical to the booming growth of modern business, which demanded more, not less, office space.

By 1964, the property had been sold to United States Steel to be demolished, and it soon became the site of the 54-story, 743-foot-high structure known today as One Liberty Plaza.

The Singer Building’s demolition is considered by some to be one of the greatest failures of the early preservation movement.

Alan Burnham, the executive director of the city’s nascent Landmark Preservation Commission filed a “meek request” asking United States Steel to consider preserving the lobby of the building,

The request had no effect, and demolition of the entire building began in August 1967.

One year later, the sight of the Singer Building’s iconic domed tower among the structures of Lower Manhattan was but a memory.

The Italian-marble surfacing and the bronze medallions with the Singer monogram were stripped from many columns and were being offered for sale.

World Largest Structure to be Intentionally Demolished

The only piece of the building which remains today are chandeliers from the lobby, which were salvaged and installed in the East Building at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn.12 The loss of the structure has been described as the “city’s greatest loss since Penn Station” by the AIA Guide to New York City.13The Singer Building’s demolition is considered by some to be one of the greatest failures of the early preservation movement. In 2005, Christopher Gray, who writes about the city’s architectural history for The New York Times, described at least one effort to save the structure. Alan Burnham, the executive director of the city’s nascent Landmark Preservation Commission at the time, filed a “meek request” asking United States Steel to consider preserving the lobby of the building, which Mr. Gray described as “a forest of marble columns” that were “alternately rendered in the monogram of the Singer Company and, quite inventively, as a huge needle, thread and bobbin.”

The request had no effect, and demolition of the entire building began in August 1967.

One year later, the sight of the Singer Building’s iconic domed tower among the structures of Lower Manhattan was but a memory. But just a few short blocks away, construction progressed on the city’s new financial center, the World Trade Center, which would have its own history as part of the world’s most famous skyline.

So as the head of the LPC spoke like a businessman rather than a preservationist, demolition continued. On March 27, 1968 it was well under way. “Yesterday the lobby looked as if a bomb had hit it,” remarked The New York Times. “The Italian-marble surfacing and the bronze medallions with the Singer monogram were stripped from many columns and were being offered for sale.

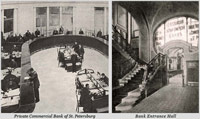

Singer House 1902-1904

Singer House (1904)

Use: regional headquarters.

Location: Nevsky Prospekt, St Petersburg, Russia.

Architect: Pavel Yulievich Suzor. Sculptors: A. G. Adamson, A. L. Ober.

Client: the Singer Sewing Machine Company.

Style: Art Nouveau.

28 Nevsky Prospect

The site at the intersection of Nevsky Prospekt and the Griboedov Canal, opposite Kazan Cathedral, was the location of the riding school of Duke Ernst Johann von Biron, the powerful favourite of Empress Anna. When this building burnt down, it was replaced by three-storey residential building. In 1902, the plot of land was bought for a million rubles by Singer Manufacturing Company

Singer Headquarters Building Problems

The company wanted a building similar to the skyscraper that was then being constructed for them in New York.

However, St. Petersburg's strict building codes dictated that no building could be higher than 23.5 meters at the cornice did not allow structures taller than the Winter Palace, residence of the emperor.

New York Type Skyscraper

The company had planned to build an 11-story building in the style of New York skyscrapers

Russian architect Pavel Suzor, who was in charge of construction, found an elegant way solution—the building’s six floors do not exceed the maximum altitude,

But there was a get-out – the rule didn't apply to spires or turrets

the ethereal 2,8 m tower with its glass globe on the corner creates a sense of skyward motion , however doesn’t overshadow the Kazan Cathedral

It is created by the Estonian artist Amandus Adamson

Atlas Statue

The decorative turret which crowns the Singer Building.

The Bald Eagle at the base symbolizes the United States.

Above we see two seamstresses clasping a globe – a figurative symbol of Singer's success in distributing its sewing-machinery around the world.

The glass globe on top of the cupola, held up by two women, represented the multinational scope of the company, whose largest foreign market at the beginning of the 20th century was in Russia

Originally had the Singer Equatorial Strip

The name of the company in large Cyrillic letters on the equatorial strip circling the glass globe above the cupola

symbolized the global reach of the Singer sewing machine.

Went away with the confiscation of Singer assets after the October Revoltion

Modern Technology in St Petersburg

It was the first building in St. Petersburg to use a metal frame, which made possible the huge windows on the ground floor.

Another first for St. Petersburg was the glass-roofed atrium,

and the building was equipped with the latest lifts,

heating and air-conditioning

and an automatic system for clearing snow from the roof.

The building was the first business center in Russia with trading, banking premises and offices for rent.

Inside the Singer Building

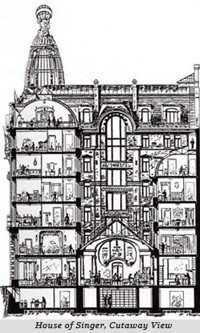

The 1906 cutaway view of the House of Singer reveals the interior of the building, including the basement below street level.

The seamstresses working for the company were visible from the street through the large windows, serving as live advertisements.

Executive Offices

On the top floor was the executive office of the Singer Manufacturing Joint-Stock Company in Russia. It had a long skylight which provided natural light to the oval shaped hall.

The large windows offered the senior staff a bird’s eye view of Petersburg, which could be said to represent the panoptic power of the company

Other Commercial Enterprises

They were leased to foreign and Russian banks and various other commercial enterprises between 1904 and 1917.

The American consulate was located in House of Singer between 1909 and the Revolution

Bronze and Art Nouveau Decoration

Bronze Valkyrie maidens from the past,

The decorations on the building were executed in wrought bronze, a material that was new to St. Petersburg

blends beautifully with the gray and red granite of the facades.

Its exterior was decorated by six bronze female figures of martial appearance straddling ship bows, although some of them are holding spindles, emblems of the building's affiliation...

Wrought Iron Balconies

while features of the new style include the floral design of the wrought-iron balconies and grilles, which is also repeated in the interior ration.

Restauration of the Interiors 2004-2006

Officially Russian Cultural Heritage

One of the top visiting sites of St PetersburgThe Dakota 1880-84

The Dakota Apartments (also known as "The Dakota") 1880-84

Use: co-op apartment block.

Location: Upper West Side, New York, USA.

Architect: Henry J. Hardenbergh.

Client: Edward Cabot Clark

Company. Style: neo-German Renaissance.

About The Dakota:

Location: Between 72nd and 73rd streets, West Central Park, New York City

Construction: 1880-1884

Developer: Edward S. Clark (1875-1882), President of Singer Sewing Machine

Architect: Henry J. Hardenbergh

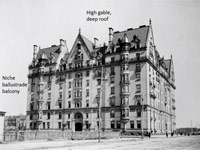

Architectural Style: Renaissance Revival— "the romanticism of the German Renaissance style"

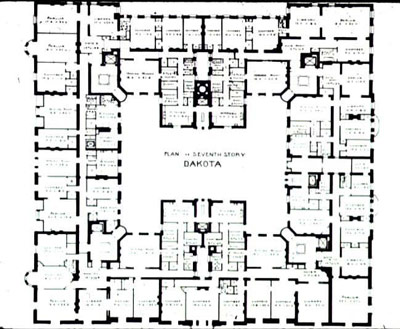

Size: 10 stories high (8 stories plus 2 attic stories under the roof); 200 feet square with center courtyard

Roof: Mansard

Construction Materials: Yellow brick, stone trim (carved Nova Scotia freestone), terra cotta ornamentation

Architectural Details: "bay and octagon windows, niches, balconies, and balustrades, with spandrels and panels in beautiful terra cotta work and heavy carved cornices"

- Edward Clarke dared to build an apartment building luxurious enough to coax the city's wealthy from their mansions downtown for ultra-modern living on what was then the swamplands of the Upper West Side.

- Redrawn plans of the entire building, published here for the first time, show how Clarke created apartments glamorous enough that they made living under a shared roof as acceptable in Manhattan as it already was in Europe's grand capitals, forever revolutionizing apartment life in NewYork city

- some of its most famous residents, including Judy Garland, Leonard Bernstein, Joe Namath, Boris Karloff, Gilda Radner, Yoko Ono, and Lauren Bacall.

- Includes reprints of several lifestyle magazine pieces showing the interiors of the apartments of dancer Rudolf Nureyev, artist Giora Novack, and designer Ward Bennett.

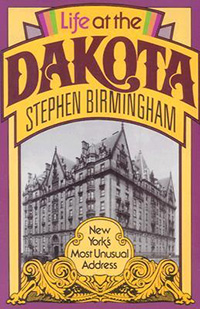

Life at the Dakota (1979) is a deliciously entertaining social history that describes the lives of the rich and trendy who have lived at the Dakota

- a New York apartment house daringly erected in 1884, "too far up" and on the wrong side of town.

- This story has the fabulous characters, sharp insights, and captivating anecdotes of Stephen Birmingham's earlier works, and the atmosphere of the elegant Dakota is so powerful that the building itself becomes an unforgettable major character.

- In this edition the author has included an afterword on John Lennon's murder at the Dakota

Not Everyone Liked the Idea

When Clark first started discussing his dreams and visions for his new apartment building, his ideas weren’t seen as revolutionary.

The idea of apartment-style living was a relatively new concept in New York City, so people were suspicious of the idea.

This is so because apartments sounded a lot like a hotel “rather disreputable places, often connected with a tavern or in…

They served a useful purpose in the 18th and early 19th Centuries, but ‘nice’ people wouldn’t choose to live in such places.”

It was not seen as a choice to rent, but rather a failure in ownership. It also seemed indecent to have a bedroom on the same floor where you would eat, drink, and socialize.

Turns out Clark was just ahead of his time.

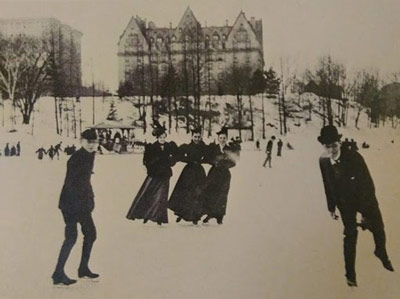

Corner of 72nd Street and Central Park West on the Wrong Side of the City

The Dakota was completed in 1884, by architect Henry J. Hardenbergh. At this point in time, "the fashionable area to live was now Murray Hill, on Madison Avenue north of Thirty-fourth Street, where a few years earlier gentlemen of fashion had gone quail hunting, though a few diehard families like the Astors still clung to their mansions on lower Fifth Avenue." The Upper West side was not yet densely populated like it is today, as not many people lived beyond 42nd Street. Edward Clark, who commissioned The Dakota, sought to change that and establish the area as a suburban connection to the frenzied downtown Manhattan [As a fashion side note, Clark was a co-founder of the Singer Sewing Machine Company. In fact, many suggest that due to the fact that this building was constructed in such an uninhabited area, it led to the nickname The Dakota, as in, it was so far away from the bustle of lower Manhattan it was as if it were built in the wild west (the Dakota territory was not yet a part of the U.S. when the Dakota was built).

The Happy Mix

Current architectural historians wrestle with putting a name to the Dakota's architectural style - calling it German Renaissance, Hanseatic town hall Chateauesque,

and even Gothic Revival, explains Miller.

"The confusion is a result of Hardenberg's mixing of historic styles; what was at the time sometimes referred to as ‘a happy mix.’"

its layout and floor plan betray a strong influence of French architectural trends in housing design that had become known in New York in the 1870s.

Most Luxurious Apartment Building with an Intellectual and Artistic Tone

However, Clark had bigger plans for the Dakota in 1880 and commissioned the most luxurious apartment building in New York City in terms of room size, opulent interiors, and property amenities.

He payed an unprecedented 2 million dollars to complete the project,( projected for 1 million , equivalent of 24 m today ) and the result would be an elaborate, eclectic architectural mix.

The kind of tenants the building attracted were not the usual old money social strivers. The Dakota’s residents "conveyed a vaguely intellectual and artistic tone".

On the other hand, the Steinways, of Steinway Pianos, were some of the Dakota’s first residents

The Dakota Indian- Too Far Up

Got its unusual name not because "it’s far out in the Dakota’s" in regard to its distance from some parts of Manhattan.

In a meeting of a neighborhood group in 1880, before construction started, the building developer Edward Clark had proposed that the surrounding streets should be named after state names.

However, his idea was shot down by the rest of those attending the meeting, so he named his building based off of his original idea. And if you look close, on the southern facade, there is a carving of what could be understood as a Dakota Indian.

View on the Central Park

Typically, bankers, lawyers, and merchants (the amazing views of Central Park and the property’s tennis courts didn’t hurt either).

Fortress Like Building - Temperature Regulating

The Dakota is not a skyscraper and does not use the "new" method of building with a steel framework. However, iron beams along with concrete and fireproof fill, were used for partitions and flooring. Developers submitted plans for a fortress-like building:

- the foundation walls—of "Blue stone laid in cement mortar"—would be 3-4 feet thick

- the first story walls would be 2 feet (24-28 inches) thick

- walls of stories 2-4 would be 20-24 inches thick

- walls of the fifth and sixth stories would be 16-20 inches thick

- walls of the seventh story and above would be at least 1 foot thick (12-16 inches)

- External walls are 2- to 3.5-feet thick on first floor, narrowing as the building's floors go higher. The thick walls also helped regulate temperature in pre-air conditioning times.

Layered Sandwich Mud for Each Brik Flooring

The nine-story Dakota still stands out among its posh neighbors.the 54 suites ranged from 5 to 20 rooms, with 500 rooms total.

Detailed stonework, reliefs, balconies, gables, and even a Native American figure adorn the outer walls.

- Each brick flooring layer sandwiches mud from the landscaping of then-new Central Park to serve dual functions of soundproofing and fireproofing. Architect Henry Hardenburgh wanted to avoid fire escapes.

Practical elements, like the service and lobby elevators (a novelty in and of themselves in the 1880s) and thick walls and floors for excellent insulation, would play an important role in comfortably accommodating tenants, while rich details like rare marble and fine wood carvings would attract a well-to-do clientele

The Carriage Way

The arched main entrance is a porte-cochère large enough for the horse-drawn carriages that once entered and allowed passengers to disembark sheltered from the weather.

Many of these carriages were housed in a multi-story stable building built in two sections, 1891–94, at the southwest corner of 77th Street and Amsterdam Avenue,

where elevators lifted them to the upper floors.

The "Dakota Stables" building was in operation as a garage until February 2007, when it was slated to be transformed by the Related Companies into a condominium residence.

Porte Cochère Gas Lamps

Original gas lamps hang by the 20-foot-high front entrance with a porte cochère

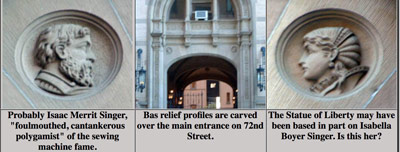

Bas Relief Profiles of Isaac Singer and his Wife

However, there are two circular portraits over the entrance at 72nd Street and another two above an arch on the Central Park West Side.

It is possible that the two above the main entrance may very well be Merritt Singer and his wife, but there other two are totally unknown.

There is a bit of mystery surrounding the identity of the two bas-relief profile portraits that adorn the main entrance, on 72nd Street — a man and a woman looking at one another across the carriageway. Who are they? In 2005, Michael Pollak of The New York Times suggested that the man is Isaac Merrit Singer, the founder of the Singer sewing machine company and business partner of the developer of the Dakota, Edward S. Clark. "Singer," Pollak wrote, "was a foulmouthed, cantankerous polygamist who acknowledged 25 children in his will, only 8 of them born of marriage. Although he and the patrician Clark detested each other, they made each other rich." Pollak speculates that the woman is "the last unfortunate Mrs. Singer," Isabella Boyer Singer, who put in a legal claim to be his widow after he died in 1875, and was supported in that claim by Clark. She won the case, moved to Paris, married a Duke and may have been one of the models for the Statue of Liberty. Notice the resemblance

Like a Mansion

It’s unclear whether the Dakota was ever a profitable enterprise

"To eradicate the stigma of 'tenements', Clark had to offer wealthy families all the amenities of a private mansion up to 16 rooms in some apartments."

when it opened, it had a staff of 150, which doesn’t include maids and cooks employed by individual households who lived in the upper floors From 1884 to 1929, all 65 of The Dakota's apartments — each with a reported four bathrooms, parlor, and servant quarters — remained spoken for.

"rents were hardly ever raised" until it became a co-op in the 1960s.

The Dakota is square building, built around a central courtyard

A lower-level dining hall that could deliver food on dumbwaiters to the apartment kitchens.

Central Heating Electricity

Print from a wood engraving of the Dakota interior from 1884, as seen in the collection of the Library of Congress

Electricity was generated by an in-house power plant, and the building has central heating.

Besides servants' quarters, there was a playroom and a gymnasium under the roof. (In later years, these spaces on the tenth floor were -for economic reasons- converted into apartments, too.)

The lot of the Dakota also comprised a garden and private croquet lawns and a tennis court behind the building between 72nd and 73rd Streets.

Courtyard

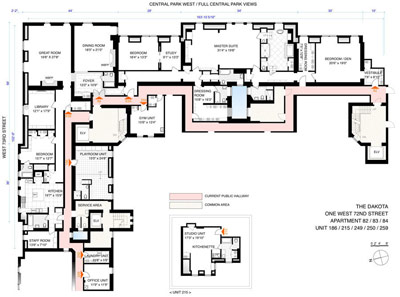

Originally, the Dakota had 65 apartments with four to twenty rooms, no two alike. These apartments are accessed by staircases and elevators placed in the four corners of the courtyard.

Separate service stairs and elevators serving the kitchens are located in mid-block.

Built to cater for the well-to-do, the Dakota featured many amenities and a modern infrastructure that was exceptional for the time. The building has a large dining hall; meals could also be sent up to the apartments by dumbwaiters

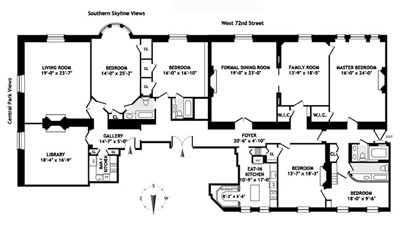

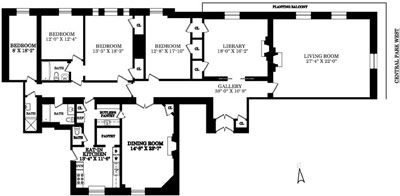

French Style of Layout

The general layout of the apartments is in the French style of the period, with all major rooms connected to each other, in enfilade, and also accessible from a hall or corridor.

The arrangement allows a natural migration for guests from one room to another, especially on festive occasions,

yet gives service staff discreet separate circulation patterns that offer service access to the main rooms.

Set the Standard of Luxury Apartment Today

Originally, the Dakota had 65 apartments with 4 to 20 rooms, no two being alike. These apartments are accessed by staircases and elevators placed in the four corners of the courtyard. Separate service stairs and elevators serving the kitchens are located in mid-block.

The principal rooms, such as parlors or the master bedroom, face the street, while the dining room, kitchen, and other auxiliary rooms are oriented toward the courtyard.

Apartments thus are aired from two sides, which was a relative novelty in Manhattan at the time. Some of the drawing rooms are 49 ft (15 m) long, and many of the ceilings are 14 ft (4.3 m) high; the floors are inlaid with mahogany oak, and cherry (Clark’s floors was famously inlaid with sterling silver).

Beautiful Detailing

Residents are forbidden throw away any original doors or fireplace mantels that they remove, and a storage area is provided for these items

Turns into a Cooperative Building in 1960s

It was in just the early 1960s when the Dakota became a co-op, and in the resultant years, Lauren Bacall, Leonard Bernstein, Rudolph Nureyev, Judy Garland, and, perhaps most famously, John Lennon and Yoko Ono became residents; the building began to take on a cult status. The movie Rosemary’s Baby, which used exterior shots of the Dakota and featured a 19-year-old Mia Farrow running around its palatial hallways (though those were filmed elsewhere), solidified the building’s fame. Then Lennon’s assassination, which occurred in the building’s archway, cemented its infamy.

Famously Rejected

Melanie Griffith and Antonio Banderas, Cher, Billy Joel, and Madonna were all famously rejected by the board.

Leonard Bernstein's former apartment was the building's most expensive sale

Located on the second floor, the four-bedroom, four-bathroom apartment had a library, a formal dining room, a wood fireplace, kitchen and breakfast areas, and views of Central park. It was listed at $25.5 million and sold for $21 million.

New York City Landmark

The Dakota was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1972, and was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

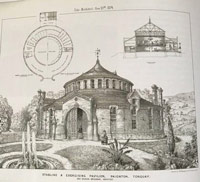

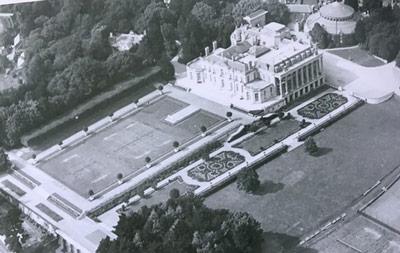

Oldway Mansion 1873

Oldway Mansion (1873; 1904-09)Use: private residence; later country club; later events venue; currently unused.

Location: Paignton, Devon, UK

Architect: George Souden Bridgman

Landscape architects: Achille and Henri Duchênes.

Clients: Isaac Merritt Singer and later Paris Singer.

Style: house: of Baroque and Neoclassical, based on Versailles and the Place de la Concorde; gardens: predominately Italianate with French influence.

Isaac Singer

He has patented Singer Sewing machine in 1851, age 41

Scandals made him leave New York. By the time he left for Europe in 1862, he had 18 children and his new wife was 30 years junior with whom he had another 6 children until the French Prussian war of 1870

By the time he came to England in 1870 , he was already one of the richest man alive.

Oldway Mansion – Isaac’s ultimate dream house

Devon seaside town Torquay, Paignton.

According to him "A proud american with a large family should live in a wigwam"

As an inventor and engineer Isaac wanted to design and choose everything from the shape of the house to the type of hinges used.

A fully working theater on the ground floor

An arena ( rotunda) a center for exercise for horses during the day, in the evening ideal venue for entertainment and dancing,with its wooden floor in place.

Wigwam -1874-75

French style Fountain between Wigwam and rotunda Aberdeen granite entrance porch Terra cotta bricks

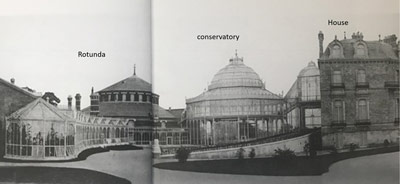

Completed after his death and owned by Isaac’s Trust Bought by Washington and Paris in 1893 from the Singer trustee

Wigwam and the Gardens after Versailles

Paris buys the house, moves in 1897 .

Engage famous landscape architects Achille and Henri Duchene, for a new drawing insired by Versaille Palace. They had just restaured gardens of Petit Trianon

Petit Versailles, Petit Trianon bis

The remodeling caused the removal of the great conversatory

1910 work was completed West front untouched Wigwam was renamed Oldway House,

Oldway Mansion

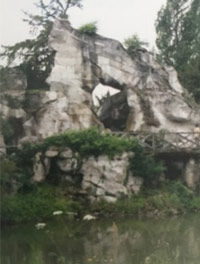

Duchene recreated each element of the garden of the Petit Trianon in Oldway,

Sphinxes, urns, satutes, prine trees, orangery , lakes with a grotto

Entrance door, Porte St Antoine of Versailles

Place de la Concorde collonades

The Crowning of Josephine et Napoleon

David’s painting , the crowning of Napoleon, bought at auction in 1898

Purchased by the French government to return it to Versailles in 1947

Hang over to the stay true original Versailles staircase.This required the removal of Isaac's theatre.

The Ambassadors' Staircase

The original in Versailles is demolished by Louis XV The other reproduction of this staircase in the world is at Bavarian Versailles, of Ludwig II, at Royal Palace on Herrenchiemsee

End of the Rotunda

Isaac Singer loved horses, had a l range of special carriages built through his lifetime.

In NY , designed and had built a canary yellow "sociable", a carriage that could accommodate 31 passangers, drawn by 9 matched horses.

Under Paris, Rotunda became a swimming pool, horse stalls becoming changing rooms

Paignton Council bought Oldway from the Singer Estate in 1946

Other buildings

The Everglades Club

(1918-19)

Use: country club.

Location: Palm Beach, Florida, USA. Architect: Addison Mizner.

Client: Paris Singer.

Style: Palm Beach, neo-Renaissance.

The Singer Factory

(1882-84)

Use: factory.

Location: Kilbowie, Clydeside, nr. Glasgow, UK.

Architect: Robert Whyte; construction by Robert McAlpine & Sons.

Client: George McKenzie, for the Singer Sewing Machine Company.

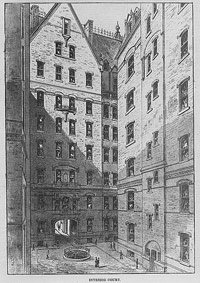

Style: Scottish Baronial.

72 rue de la Colonie (1911)

Use: social housing.

Location: 13th arrondisement, Paris, France.

Architect: Georges Vaudoyer.

Client: Les Habitations à Bon Marché (HBM).

Sponsor: Winnaretta Singer (Princesse Edmond de Polignac).

Style: cité horticole.

La Cité de Refuge

(1929-1933)

Use: social housing.

Location: 13th arrondisement, Paris, France.

Architect: le Corbusier.

Client: Fondation de l’Armée du Salut.

Sponsor: Winnaretta Singer (Princesse Edmond de Polignac).

Style: avant-garde.

The Clark Institute (1955)

Use: charitable arts foundation and museum.

Location: Williamstown, Massachusetts, USA.

Architect: Daniel Deverell Perry, Tadao Ando, Annabelle Selldorf.

Client: Mr and Mrs Robert Sterling Clark.

Style: modern.

The Nahmaschinenwerk factory,

a Singer plant in Wittenberge, designed in the neoclassical style and modified by Felix Ascher and others. There is a smaller Singer factory in Kreuzberg, Berlin, that currently has new life as a fashion and design centre.